Before we get into the fine print of Part II of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, it’s worth taking some time to look a little closer into this man and how it was that he came to be such an important figure in American history. He was 38 years old when he wrote the pamphlet, was not extensively educated, and was raised by a Quaker father and an Anglican mother. His family was by no means wealthy (his father was a corset maker), and, in his early years, he bounced around from job to job until he settled for a time, according to Britannica, working as “an officer of the excise. His duties were to hunt for smugglers and collect the excise taxes on liquor and tobacco.” In other words, he was a God-fearing blue-collar nobody from nowhere, just trying to find his way in the world.

It is written that he couldn’t hold down a job (he was fired from the excise office because of an essay he published that was apparently politically incorrect, had two failed marriages under his belt, and generally seemed to struggle to “find himself.” It is clear that he was a deeply opinionated and quite prolific writer, considering the breadth and wealth of writings he left behind after his death at the age of 72 in 1809. In many ways, you could consider him an always-trending blogger two and a half centuries before his time. And, as Britannica tells us, it would be his having met Benjamin Franklin in London, who told him he should go to America to seek his fame and fortune, that the world would have ever come to know who Thomas Paine even was. [Author’s note: Given Franklin’s well-documented propensity for frequenting taverns, I smile as I imagine these two men throwing down pints and taking turns bitching and complaining about the King and Parliament in England. I imagine, chuckling as I do so, what that looked like with seven or eight pints under their belts by the time they were done.]

Thomas Paine, it is fair to suggest, was an enigma; on the one hand, he had a deep and unbending belief in God, but he held organized religion, every bit as much as the systems of governance over societies, with the greatest of disdain. In what is said to be his last major work, “The Age of Reason”, Paine committed 45,000 words to pen and paper, attempting to point out the lack of credibility in the Bible (and other organized religion governing texts) and the degree to which he believed the top tiers of Church leaders (as he likewise felt about Kings and Elite Political leaders) manipulated the faithful with deception, half-truth, and sometimes-outright lies in order to assert and sustain their power over the rest of us. This will be a recurring theme as this series of essays unfolds in the countless entries ahead, especially when overlaid on top of the myriad crises facing not only Americans but the whole of our species under the ever-strengthening thumb of this so-called Global reset being perpetrated by a small, unelected wealthy and Elite few seeking to manage end control the futures of the overwhelmingly vast majority of the rest of us across the planet.

The deeper I dig into the story of Thomas Paine, and his contribution to the National Conversation on the matters of Freedom, Liberty, and our God-given rights to self-determination, the more clear it becomes that Common Sense is only the beginning of the story. His other Pamphlets and his so-called “Crisis Letters”, need to be considered – collectively – to fully appreciate the importance of his contribution to the reflections of our founders and our founding documents. All of this will be reviewed in Greater detail in the writings ahead but, for now, let’s move ahead into “Hereditary Succession.”

Remember that bit in the Declaration of Independence, right up front, about all men being created equal? We know from fairly recent history that America’s antagonists – both foreign and especially domestic – many people scoff at this statement while quickly and angrily citing our early history with slavery. But if you were to have put Thomas Paine’s words in the opening paragraph of Part II in Common Sense into the Declaration instead, the dynamics of modern anti-Americanism might have been quite different. You might want to read this next paragraph twice.

“Mankind being originally equals in the order of creation, the equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance; the distinctions of rich, and poor, may in a great measure be accounted for, and that without having recourse to the harsh ill sounding names of oppression and avarice. Oppression is often the consequence, but seldom or never the means of riches; and though avarice will preserve a man from being necessitously poor, it generally makes him too timorous to be wealthy.”

In the second paragraph, he goes on to suggest that “there is another and greater distinction for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of men into kings and subjects. Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth enquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind”. These words were written in the times of a despotic King, or at least corrupt; if we consider modern American elites and the assorted and sundry unelected ruling classes, the same questions can be asked today just as fairly as Paine considered them in 1776.

As I whistle past the graveyard of the currently vitriolic commentary on the distinctions of nature, Paine’s dissertation on the matter of men (and women in our modern era) and this idea of hereditary succession is worth considering. Held above the rest of us just for having been born, even before having accomplished anything worthy of higher standing than anyone else, is anathema to everything a meritocracy(which America is, despite all of the gnashing of teeth these days) was designed to represent. While it may be true that America’s system of governance explicitly rejects any attempt at installing a monarchy within our body of laws and rights, there is certainly a monarchy of sorts within our representative Republic all the same.

The list of billionaires in America is long and grows by the day, as does the number of powerful and influential fill-in-the-blank former government officials, celebrities, and political and socio-cultural thought leaders. Yet, as happy as the most gracious among us might be for their success and good fortune, this tiny percentage of the overall population is completely in control – even if only behind the scenes and out of public purview – and has their hands on, or at least a substantial degree of influence over, every lever of power that directly affects the lives and livelihoods of every one of the rest of the nation. And as they procreate, their progeny takes their first breaths, already possessing more wealth, power, and influence (or access to it) than any of the rest of us are likely to create of our own accord.

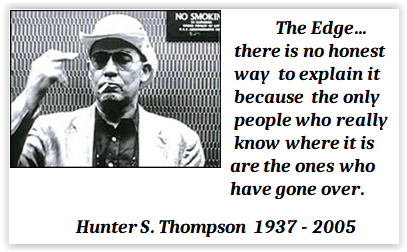

Paine commits quite a few words in the middle 1/3 of Part II recounting the biblical story of how the Israelites came to decide they wanted a King to rule over them, making the case that this decision brought about not only the fall of the Israelites but also set the precedent that has ravaged the civilizations, globally, in the many Millennia since. In my first book, contributing author “Vassar Bushmills” provided a lengthy dissertation titled “Man’s Thirst For Kings”. He discussed at some length much of what Paine alluded to in Common Sense, going into much greater detail on the various histories behind the rise and fall of Kings, including but not limited to the histories behind the English Kings.

With the luxury of two and a half more centuries of observations on human nature, Vassar was free to touch on that one nerve about us that Paine wouldn’t have dared to tread, taking care not to offend his audience. While it is true and has been proven that, everywhere it’s tried, we live far better in the absence of a King than we do under the thumb of one, our own vanities and self-indulgences sooner or later lead us back to the edge of our own self-destruction every time we make a mess of things that we don’t think we can solve on our own. Vassar puts it this way: “What we learn, early on in the Old Testament, is that this thirst to be free is conditional; it’s a lot stronger when freedom is denied and a lot less strong when freedom is literally there for the plucking, like fruit from a tree.”

Even though Paine didn’t say the quiet part out loud about the many thousands of years our species has allowed itself to delegate the powers of Freedom, Liberty, and self-determination to the whim and fancy of others, he nonetheless articulates quite well the price our descendants are forced to pay for our sins wherever we willingly subject ourselves to slavery and subjugation. Almost without fail, the more tightly we cling to whatever is familiar – even if it is oppressive and causes us great suffering and misery – societies are inclined to allow themselves to continue suffering rather than effect any sort of major change. And, to put a finer point on this, does this ring a bell?

“Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.”

Toward the end, Paine offers an interesting point worth considering, not only about Kings, but about leaders more generally, as he suggests this: “But it is not so much the absurdity as the evil of hereditary succession which concerns mankind. Did it ensure a race of good and wise men it would have the seal of divine authority, but as it opens a door to the foolish, the wicked, and the improper, it hath in it the nature of oppression. Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent; selected from the rest of mankind their minds are early poisoned by importance; the world they act in differs so materially from the world at large that they have but little opportunity of knowing its true interests, and when they succeed to the government are frequently the most ignorant and unfit of any throughout the dominions.”

Paine certainly understood that the excesses of England’s King and Parliament had finally pushed the American colonies into a corner, and, using his Common Sense pamphlet, he made that case to the American colonists. Once the battles of Lexington and Concord had taken place, he made it abundantly clear that the choice being presented to the people was, as it has always been throughout the history of mankind, having to choose between the lesser of two evils.

It saddens me to know that, with so many great things America has accomplished in the two and a half centuries since we parted ways with England – in far too many ways – we still find ourselves looking at our leaders… Assessing the things they have done for us or done to us, and still find ourselves having to consider who we will vote for in the upcoming elections, being forced to choose between who sucks and who sucks less. I’m not so sure we’ve made nearly as much progress as we could have since the last time we went through this process, but God willing, we will start considering who has betrayed our faith America and who continues to sustain and nourish it.

It is said that wisdom is “the quality of having experience, knowledge, and good judgment. “ I am of the opinion that there are far more people in the world that consider themselves "lovers of wisdom" (philosophers) than there are those that actually possess it.

At her founding, the American Nation had already amassed 150 years of " national" wisdom; our first-of-its-kind Nation, built from the bottom up (as opposed to the top-down construction of every previous nation in humankind's history), and the Framers understood that the single-most-important ingredient necessary for her long-term survival was the freedom, liberty, and right to self-determination of the Sovereign Individual of which she would necessarily be comprised.

Join us, or follow along as we take a closer look at these notions.

It is said that wisdom is “the quality of having experience, knowledge, and good judgment. “ I am of the opinion that there are far more people in the world that consider themselves "lovers of wisdom" (philosophers) than there are those that actually possess it.

At her founding, the American Nation had already amassed 150 years of " national" wisdom; our first-of-its-kind Nation, built from the bottom up (as opposed to the top-down construction of every previous nation in humankind's history), and the Framers understood that the single-most-important ingredient necessary for her long-term survival was the freedom, liberty, and right to self-determination of the Sovereign Individual of which she would necessarily be comprised.

Join us, or follow along as we take a closer look at these notions.

Vassar Bushmills

Vassar Bushmills

Add comment